Passing the unlit kiln, crossing the lab strewn with colorful pottery, and pulling the sealed door that looks like it belongs in a bank, I can safely escape the noises that are chasing me. After breathlessly introducing each student work that was on display at the sale, the intention behind it, the clay used, the challenging attempts contained in it, and even the plans for the future, I quickly smoke a cigarette like a young man and sneak into the lab.

The atmosphere here is quite different, with one side being a home, the other a scholar’s secret underground laboratory, and the other a familiar workshop-like studio. There is no hair, but the first thing that catches your eye is the experimental shelf. There are still living, breathing lumps of clay from all over the country, and a lot of experimental specimens baked with various compositions of clay and glaze. In the work space inside, an electric potter’s wheel and freshly turned bowls are slowly ripening.

Unlike me, who was sniffing around the secret laboratory, the two of them were now in a completely different time. The potter stood still, his body still, and opened the tea with restrained movements, while the interviewer sat in front of him, his hands clasped together and meditating. The sound of the fire being struck in the bowl permeated the air like a wooden gong. A fragrant smell filled the room.

(1) Treasure No. 1437 ‘White Porcelain Moon Jar’. Height 41cm, mouth diameter 20cm, bottom diameter 16cm, body diameter 40cm

Dae-cheol: I was deeply impressed when I read Kim Hoon's <Song of the Sword>. It starts with the sentence , "Flowers bloomed on every abandoned island." Later, the author said in his essay <Message to the Sea> that he spent the whole day pondering the words "Flowers bloomed" and "Flowers bloomed . " "Flowers bloomed" is a physical fact and an objective description of the world, but when you write "Flowers bloomed," you are conveying the opinions and emotions of the person reading. That's when I realized that the thoughts and emotions contained in a piece of writing can change completely with just one letter. I didn't know that people could be this detailed and thorough in their work.

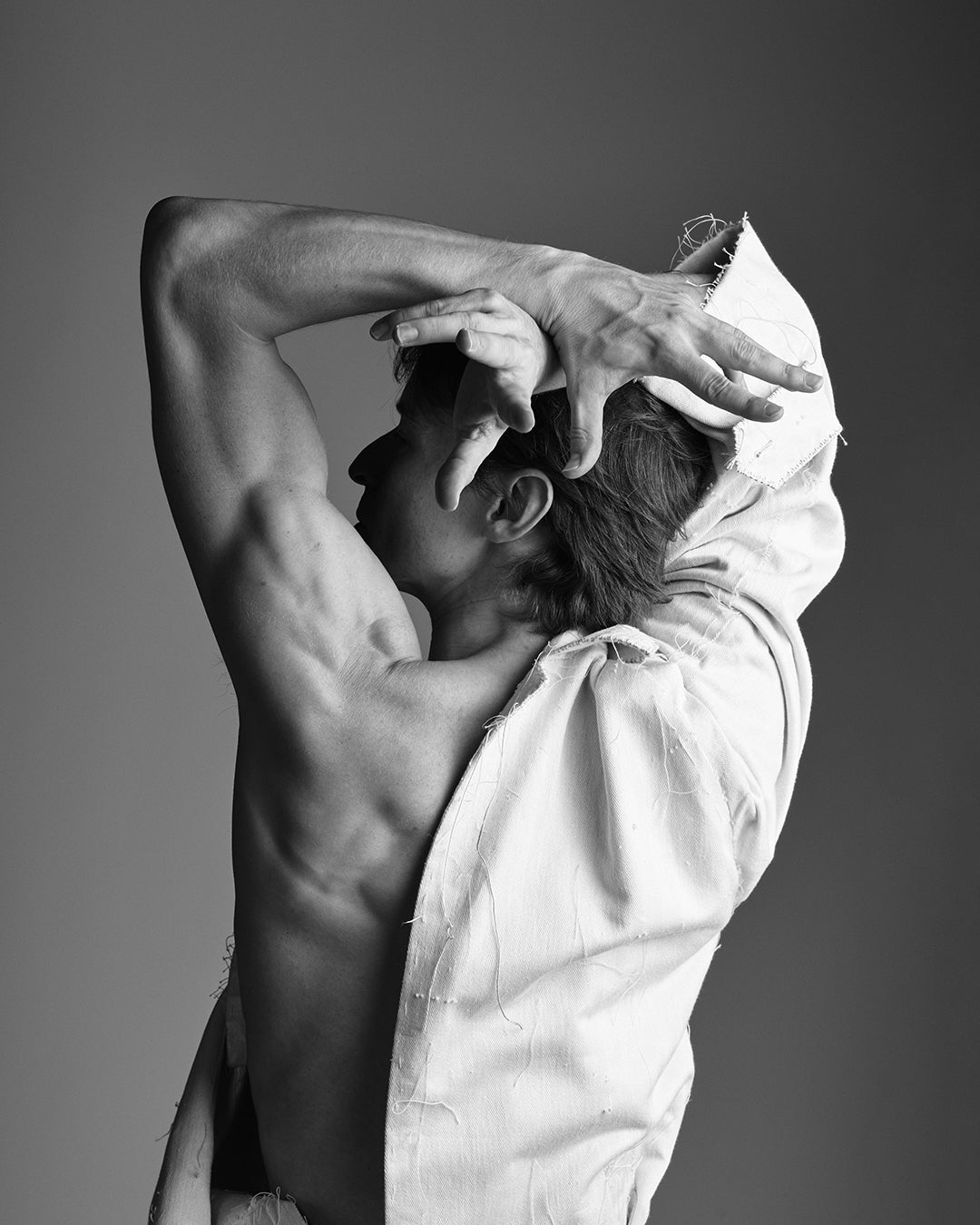

I think that creating something is all like that. I often think that the attitude you have toward your work is important. It's really amazing that you can look into things and think about them that much. He's a person who writes with words, and he looks at the world with a completely different attitude from his position. Likewise, you're a person who makes pottery with clay, and we're people who make clothes with fabric, so I think there are similar points and attitudes.

Jeong Yong: There is something special about our white porcelain and celadon when I look at them. During the Joseon Dynasty, kilns were divided into folk kilns that made commoners’ wares and government kilns that were managed by the government. Most good white porcelain was made in government kilns. Clean white porcelain clay was precious. It had to be dug up with a knife, handful by handful, from the iron-free ore veins and carried all the way to Gwangju. The roads were not well-maintained, and when the rivers were blocked, they had to be carried on a back on the mountain path. The clay that was collected with difficulty was then subjected to impurities and discolorations, coarse particles were filtered out, and it was aged to increase its viscosity. Then it was fired in a wood-fired kiln where the temperature could not be controlled.

It’s not like potters were a special position. They were just commoners who were drafted in order to do labor. Even if they didn’t want to, they had to do it out of obligation. When the government called them during the busy farming season, they had to go make pottery even if their wives and children were starving. It’s amazing that moon jars came out in this environment. Think about it. They’re huge. They gathered that much precious white porcelain clay and put it in a wood-fired kiln. If you go to the white porcelain room of our National Museum, you’ll see a really huge moon jar (1) . Compared to today, it would have been about the same as launching a Naro rocket.

It was an environment where the overall level could not be good. But among them, some outstanding ones suddenly stand out. They break through the standards of the time and stand out. I’m not just talking about national treasures or treasures. In such poor environments and situations, amazing results that surpass the level of hard work often emerge. I call that dedication. It’s not like these people could make money or achieve fame just because they made this well. Despite the fateful status and hardships inherited from blood, if a surprising and special result is produced when viewed as an object in itself, then this can only be called dedication.

Daecheol: Isn't it immersion? For a moment, forgetting your own situation, without any sense of your own situation or position, just purely concentrating on the work, entering the mental realm, and being satisfied with the level of completion.

Jeongyong: Yes. Even if the work is hard, there is definitely joy in it. The person who touches the clay must have been happy when he made it well, the person who turns the potter's wheel must have been happy when the pottery was well turned, and the person who fired the kiln must have been happy when the temperature was well maintained and the vessel came out intact. That joy is still being passed on to this day. However, there are times when you can see traces that go beyond joy and can only be called devotion.

Daecheol: Even in such an unreasonable situation, there were people who felt small joys in their work, discovered small things in it, and finally concentrated to the point of unconsciousness, and thanks to that dedication, there were objects that blossomed without any intention or concept. However, it was Japan and the West that first looked at and discovered the value of our ceramics. I think that apart from the dedication to making them, the viewer should also be able to look deeply and savor them.

Jeong Yong: Yes, honestly, I can't say that all of Joseon porcelain was good. It's a shame. Official kiln white porcelain is really good. At least it was produced in a managed and controlled environment. However, when you look at the utensils that were used by ordinary people, there are many that are poorly made. They are thick, rough, and have scratches in the places where food was placed, making them unsanitary. I can't help but think that if they had just been a little more careful, they could have been made pretty. Choi Sun-woo and Ko Yo-seop said about this, "Joseon people lack follow-up skills."

I think that ceramics should have been brought in as an industry. Japan, which used to place orders for our kilns, eventually became wealthy through the ceramics industry. The story of Joseon potter Yi Sam-pyeong is famous. During the Imjin War, he went to Japan, received a samurai title, started a life as a potter, and eventually discovered white porcelain materials in Arita and started a local industry. Even now, the 'Dojo Yi Sam-pyeong Monument' stands on a mountain overlooking Arita City, and he is enshrined in a shrine, and a memorial service is held every year on the anniversary of his death. However, Joseon ceramics declined, and by the end of the 19th century, at best, they were making pottery pots and subcontracting to the Japanese.

Our modern ceramics also had a long time to figure out. After the war, the government sent our ceramic artists to study abroad in the United States. To be exact, they studied the so-called Abstract Expressionism movement, which was centered in California at the time. The influence of people like Jackson Pollock was already influencing American ceramics majors, and the first generation of our university professors learned about it. After that, so-called plastic ceramics, artistic ceramics, were taught in our university education for a while. However, considering our economic situation and the size of our housing at the time, there weren’t many spaces that could accommodate such artistic objects. This meant that no matter how many works we made, we couldn’t sell them. I think that work that only a very small number of artists could do took up a large portion of university education.

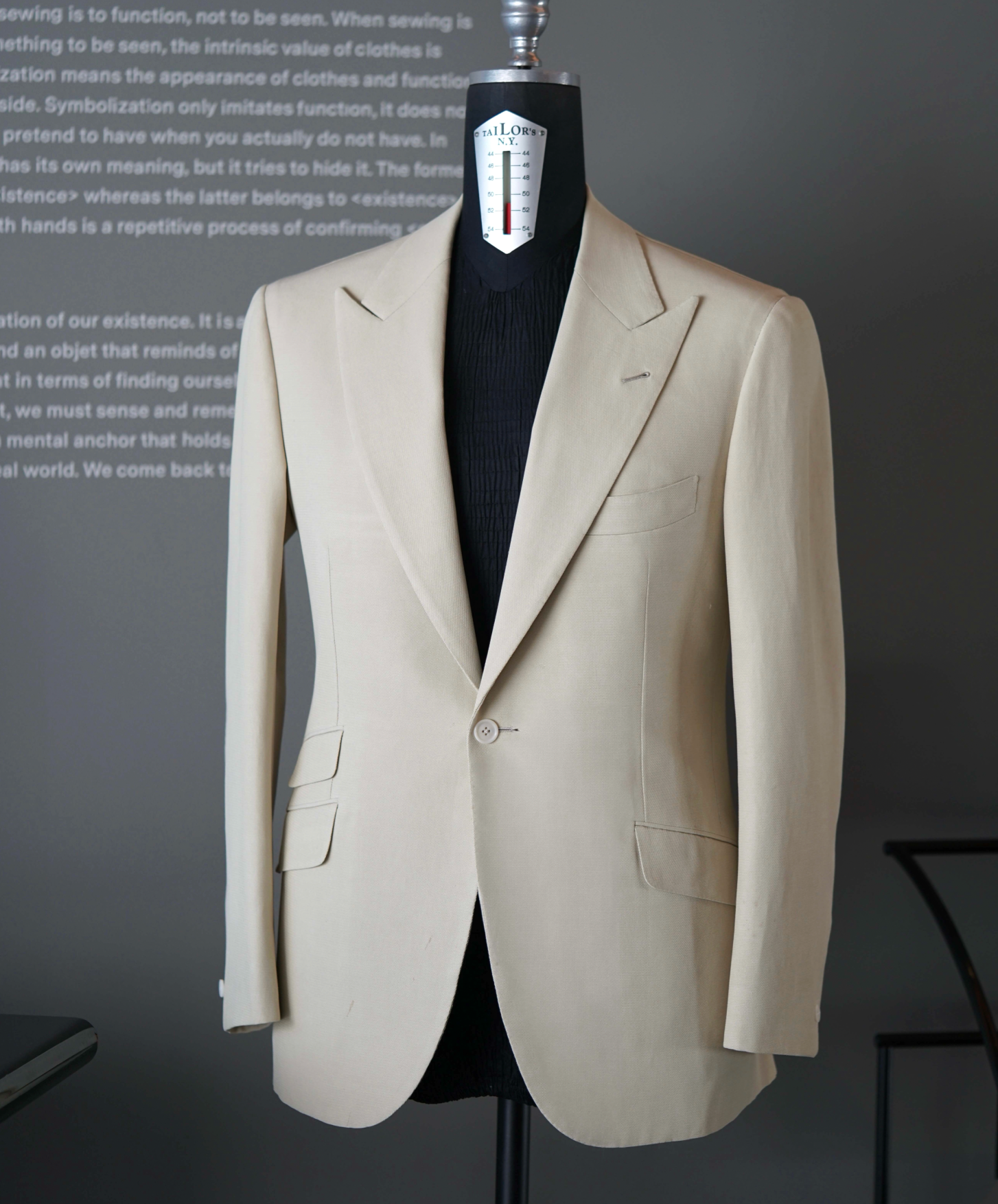

Daecheol: When I first encountered your work, it was mostly white porcelain with a refined and restrained power. The way you connected the touch and lines was so calm and clean that it was hard to put into words, so it felt a bit sharp. I remember that it had a strong architectural atmosphere and formativeness, and there was also a contrast and clarity in the edges. It also felt modern, but strangely connected to the past. Did that kind of work come from the same sense of concern?

Jeong Yong: My white porcelain work comes from the imagination of 'what would it look like now if Joseon porcelain had developed along a continuous context at that time?' I capture some unique shapes or interesting ideas that catch the eye and add modern imagination to the context there. What we often overlook when we talk about future-oriented stories is the context of step-by-step development. I think we shouldn't stop at the level of importing only parts out of context or reproducing old things as they are.

I want to rediscover, one by one, the values that were once considered precious and lovely in our past, but have been forgotten and overlooked over time, in the place where I live now. Every time I look at the vessels that are filled with such dedication that they are touching, 'How could this be here, how could such a work exist in such an era?' I am most curious about what to do. Those questions and curiosity are the driving force behind my ceramics work.

Daecheol: But when I look at the bowls you’ve been working on recently, they feel very raw. They seem to have been thrown out, and the materials are in various colors and uncontrolled states. It feels very different from your previous works, so maybe you could say that your work has progressed to the next stage.

Jeong Yong: It’s an embarrassing story. Actually, I was always interested in bowls while I was working on white porcelain. But I couldn’t keep them because I thought they were lacking. I really liked bowls and tea since I was young, so I went around getting tea from various places. And I drank a lot of bowls made by famous craftsmen and antiques. I even went out of my way to collect bowls that I really liked.

I guess my standards have become higher. There are antiques in my room, and there are many bowls made by people who have been making them for a long time. If I were to secretly put my own next to those works, I would feel so embarrassed that I couldn’t leave them. But now, I’m trying to make them and use them with the intention of saving them and collecting my own. Maybe that’s why you think I’m working on bowls these days.

If my previous works had to be elaborate and technically well-matched, Sabal is more free and I work according to my inspiration. While I am used to working elaborately for a long time, I expect that working on a work with a completely different form, energy, and characteristics might be a kind of antithesis. I am moving forward by overlapping and accumulating opposing experiences.

Daecheol: The reason I felt bowls were special was because, unlike other ceramics that tend to exist as decoration, bowls are meant to be put to the mouth. At first glance, you can feel the meaning or emotion of the shape, and you can feel the temperature of the clay by touching it, but in the end, the important thing is the act of putting it to the mouth and tasting it. The dishes that touch the mouth seem very direct. Is there anything that you find particularly difficult or pay attention to when making bowls?

Jeongyong: You know Ido-dawan. It's a tea bowl that is considered a national treasure of Japan. Even if you look at it purely without thinking about the backstory of the tea bowl being exchanged for a castle, it is truly beautiful. There are parts that can never be said to be complete as an object, but people like it too. There aren't many left, and many people want to keep them, so many people try to reproduce the form. From that beauty, a fixed idea about the bowl was created, and now a kind of standard that sets the shape of the bowl has been created.

In comparison, the things I make are so-called 'flying bowls'. They don't conform to the standard form. Instead, I always think of the "six methods of painting" in oriental painting. These are six important methods that have been passed down since the Southern and Northern Dynasties period in China to be followed when painting. The most important part of them is the vitality and movement of energy. 'The painting and the ink must be lively and vibrant.' I think that's exactly what a bowl is like. It's good to follow the example of a single case, such as Jeongho Tea Bowl or Ido Tea Bowl, but at least for me, it's more important to create something that is lively.

Some people express energy, power, and life, and emotionally, it can be expressed as the scent of a human being. From that perspective, I keep looking at the things I make. Are they really vibrant? Do they have enough energy? The reason I compare them with good antiques or works by my favorite artists is that it is a way to feel it more intuitively. If they look too shabby when compared like that, I think they are not vibrant.

Daecheol: The value that is worth exchanging for a performance may not have come from just the norm. The objects that moved people at the time and left a mark on their hearts have come down through the ages as so-called 'famous items', and they still exert their extraordinary power to this day.

I think the reason Japan was able to develop ceramics as an industry was because they had a language to read beauty. They defined beauty as “date,” “iki,” “wabi,” and “sabi” by era, and systematically organized their appreciation. That asset constitutes today’s Japonism. In the United States alone, after World War II, many galleries opened up, and unparalleled critics like Clement Greenberg emerged, opening up a way to approach art. They were given an opportunity to expand their thinking.

We only have easy words. There are only a few vague expressions like 'Korean-style elegant lines' and 'elegant form'. Beauty is energy and poetry, but if you just scatter it into a few expressions, it disappears before it reaches the emotions. There are definitely things that create beauty, and there are people who are dedicated to digging into the smallest details that are unimaginable, but I don't think there are many people who can approach the facts directly. Rather than looking at the object itself, I think they rely on the background drama and safe norms. They can't look at it emotionally. Since there is no one to look at it, the people who feel it and create it no longer have the strength, and other possibilities don't bloom.

Jeong Yong: Now that you mention it, I remember learning poetry in Korean class when I was young. They would break down sentences into factors and teach us what the "correct answer" was. It was like trimming a bonsai tree, cutting off all the buds of possibility and cutting them off nicely.

Since my job is to create, I am careful about saying too much. When I put all sorts of things into my work, there are times when things don’t make sense within me. I focus on understanding the materials, imagining certain expressions, and making them concretely. For example, when it comes to bowls, Ido tea bowls, or anything else, the time I spend looking at them is probably several times longer than the time I spend making them. Rather than defining and understanding them with words, I am someone who feels with my senses and emotionally interprets the countless images that come to me as they pass by. I think about why something looks good and why this looks cramped, why it used to be good but now it’s not so good, and why some things look better after having different experiences.

As you said, I think there is a lack of proper language and good explanation. But I think we should also think about how close the so-called culture is to us. Whether it is ceramics or music, how many Seoul citizens spend time at least once a year at a concert or an art gallery? The city of Seoul is a place to work, and it is a space efficiently designed to fit that purpose, so it is difficult to feel cultural leisure. People are always busy, and their attention would have difficulty reaching places like this.

The positive thing is that we hold a sales exhibition (at Seoul National University Ceramics) every year, and the number of people who come with interest is increasing year by year. It means that there are more pleasant possibilities. I think that modern people have a thirst, and it starts from this point. More important than a good explanation is the interest of the subject who wants to understand. With that interest, you can secure time to look, and as you look, the depth of understanding increases little by little, and as you do that, you will gain the ability to interpret on your own, and as the interpretations gather, another world will soon open up.

I once saw a documentary about the sushi master Jiro in a theater. He makes a plate of sushi that costs about 40,000 yen in a very narrow underground shopping mall, and there are people who come all the way there to eat it. What do they see there? Maybe it’s just a few percent difference. Just a few percent tastier, just a few percent better. But there are people who are so happy to find that small difference. Isn’t Lerici the same? People who have the eye to see that small difference and have well-trained emotions come to find it. I think that the development of a country’s culture and craftsmanship is guaranteed when such people increase, and they disappear when the members of society don’t have time to devote to that small difference.

Daecheol: That's right. It takes too much time to make a difference of just a few percent. In business, there are certain methods that must be followed. In order to make profits and survive, time must be saved at all costs, and there are clear limits to production and raw materials. It is impossible to cross that line with one's own will. If you want to challenge it, you have to change everything from the beginning. If you follow their methods, you can only make the same products as them, so you have to pioneer a completely different path. However, even those small differences of a few percent can be felt by the human senses, and eventually, there are elements that touch the heart and make you think, "This is different." If you don't know that, you shouldn't make it so difficult.

Jeong Yong: I think what's needed at that time is discernment. I don't think discernment is such a great word. Even if you boil a single ramen, knowing how to make the noodles can be discernment. It starts from the small part of understanding and being considerate of such trivial things. I don't think you can gain discernment through some kind of amazing education. I think really good teachers are those who open up. I think one of the roles of a teacher is to talk about things they've seen, to create empathy, and to open up a perspective that allows them to think for themselves.

Limited dialogue , Dae-cheol Kim