Greek rhetoric, which studied everything for persuasion, is not simply the art of public speaking. Aristotle defined rhetoric as "the ability to find all possible means of persuasion in a given case," and included rational (logos) texts, the audience's emotions (pathos), and even the speaker's character (ethos) in the realm of rhetoric. All of these are means of persuasion.

Dressing for the mood requires a kind of rhetorical understanding. Everything we have, even if we try to hide it, always conveys a meaning. It reads clearly like language. Each tiny element is a word, and they combine to form a sentence called the mood. Think of the elements that affect a person’s impression. Posture, eating habits, gait, facial expression, eye movement, gestures, clothing, hairstyle, tone of voice, words used, manner of speaking, thought patterns and thoughts expressed in sentences, scents and body odors, cleanliness, the type and condition of belongings, the attitude of consideration for others, the way silence is used…

This nonverbal form of speaking is powerful. It's very emotional, very ethos, and sometimes symbolic. Why did Steve Jobs, who always wore a suit, suddenly show up for a presentation wearing jeans and New Balance? It's because he had something to say. You're on the podium every moment. You have to convince people in the most authentic way possible.

If there is a rhetoric of dressing as a nonverbal eloquence, there is also a way to read a suit. There are texts in the form of clothes that are readable, but there are also contexts that cannot be read if you do not know them. So rather than blindly wearing whatever others say is good, it is better to slowly look at it and develop the ability to read it properly.

The suit is the most masculine clothing. Therefore, it can be said to be part of the rhetoric that has developed to express masculinity. The different views on the suit can be seen as coming from the 'consensus of each culture on the ideal masculinity'. Now, let's compare the UK and Italy, which have a long historical tradition. The two suits are classics that clearly show the evolution of men's clothing based on different masculinity.

John Bull, national personification of Great Britain, 1914 ©

The identity of British men, the gentleman

The classic British suit is generally characterized by a neat and angular shape like a uniform, with rough stitching, and is often described as having a plain feel compared to the Italian suit that followed. This is because such a suit design was thought to best fit the British identity. What was most important to the British at the time was 'what is Britishness?'

Professor Park Ji-hyang mentions the symbolic Englishman, John Bull, at the very beginning of 『 British, All Too British 』. The 18th century British celebrated their imperial success and tried to define how Britain could succeed and what it meant to be 'British'. The self-portrait drawn in this way is the gentleman. The gentleman as " a British man who practices diligence and self-deprecation, is quiet and serious " was born at this time.

Originally, this word referred to the gentry, a class in feudal England. The gentry were not a high class like nobles or knights, but they were common landowners who owned land and formed their own families. They took real power in society based on the wealth they accumulated in the process of dismantling the feudal order. Like the bourgeoisie, it was a name with a strong class meaning of 'not having to work to live', but rather than being eliminated during the revolution, it was established as the most desirable self-portrait of modern England. This was something that was hard to find in other nation-states.

The gentry behaved differently. Rather than trying to overthrow the existing order, they created new social roles. They absorbed the lost spirit of chivalry, taking the lead in battles and performing social duties such as unpaid service and charity. From contemporary novels such as Dickens’s Great Expectations (1860–61 ), people learned what was and was not gentlemanly. A gentleman is reserved and conceals his emotions. He acts with dignity and propriety, discerns and restrains himself from doing what he ought not to do. He does his duty and labor as a citizen, and is loyal to his country and the institutions to which he belongs.

The new identity is accepted as a socially desirable value. The social elite actively utilized the image of the gentleman, and even the working class voluntarily tried to acquire gentlemanly values. In the movie Kingsman (2014) , there is an explicit line that says, "A suit is a gentleman's armor, and a gentleman is a modern-day knight." It is very similar to the encouragement that regardless of one's origin, one can become a gentleman if one works hard. The movie exaggerates and caricatures the noble gentleman, but ultimately depicts the process of the lower-class protagonist growing into a gentleman.

The traces of the old chivalric spirit that became the spiritual foundation of gentlemen are still clearly imprinted in sportsmanship. England is the birthplace of modern sports. In medieval matches where players had to kill each other, they set up referees and emphasized the spirit of fair play, accepting defeat bravely and victory humbly under the rules announced in advance. That is the attitude of a gentleman and the meaning of desirable masculinity.

The masculinity of the British is a historical identity that the British themselves established during the process of forming a modern nation. Compared to Italian suits, which are full of artistic and material beauty, British suits are extremely spiritual clothes, and cannot be properly read without understanding the spiritual culture of the British. For them, the expression of identity is much more important than the perfection or visual beauty of the suit. This is because the aesthetic sense of the British is the gentlemanly attitude itself.

Sensation Young British Artists from the Saatchi Collection, Brooklyn Museum, 1999

British suits, a reflection of spiritual culture

Those who like the delicate and elegant craftsmanship of Italian suits may be a bit disappointed when they see British suits. This is because they value practicality and formality more than craftsmanship and beauty. I once went to all the stores in Savile Row and tried on clothes, but I remember that they all lacked craftsmanship. Rather than feeling delicate emotions in sewing, I got the strong impression that they consciously restrained themselves from 'decorating things too meticulously and densely'.

This attitude comes from the value of manliness. At the time, the British interpreted that their imperial achievements could be derived from masculine qualities. Park Ji-hyang points out that manliness was the value and ideal of middle-class men, and the most cherished value. This manliness is a crude quality that does not correspond to sophistication or sociality. With the addition of a ‘manly’ aesthetic that prioritizes practicality and making without worrying about details, it was created in a style similar to a uniform.

On the British pragmatism and aesthetic indifference, Park Ji-hyang quotes the German-born British art historian Nicholas Pevsner: "There are no Michelangelos, Dürers, or Velazquez in Britain, because the British national character values practical sense, reason, and tolerance. The moment they acquired tolerance and a spirit of fair play, they lost the intensity that could bring out the greatest in art."

However, in this way of understanding, we must be wary of remaining at a superficial and fragmentary level of complex cultural and historical results. It is not enough to simply distinguish between Italian and British clothing and take sides or imitate one side. Learning from the other naturally involves self-reflection.

In Britain, where tradition seemed to be valued, the boundaries of all expressions are rapidly collapsing, led by the YBAs. There is no one thing that speaks of the whole, or a distinction based on fragmentary characteristics. The traditional concepts of exhibiting art in a gallery or selling clothes in a boutique are all being accepted as trite. Now, inspiration from poetry, literature, visual art, and music are being connected and integrated into everything.

Does that mean that the identity of Britain is completely changing? Not at all. Rather, because the identity of Britain is firmly established, such changes and progress are possible. It is only a formality established according to the spirit from the beginning, and even if the formality is dismantled and the form is integrated according to the changing times, the essence does not change.

So we should not make the mistake of focusing only on either historical form or today's innovation. We should stop the habit of constantly changing our own identity while accepting the rapid changes in the world. We should read properly, be able to see the essence, and at the same time think about what 'self' really is. From that, a new spiritual culture and a new history can begin.

Michelangelo's David

Classic Italian masculinity

When I hear the word 'masculine beauty', I first think of ancient statues like David or Adonis. Since ancient times, the most ideal beauty of the human body has been carved into unchanging stone. We feel an irresistible charm from the perfect three-dimensionality and proportion of precise statues. Italy is a country that has preserved the classical aesthetics of ancient Greece and Rome, and the Renaissance. Their masculinity comes from wonderful proportions and rich three-dimensionality.

Actually, it’s a bit difficult to limit this story to Italy. After all, Greco-Roman culture is the origin of the West. Western art tends to see a wide, firm chest as the archetype of masculinity. Take a close look at statues that give off a sense of masculinity. You’ll definitely find some commonalities. How about the way male heroes are depicted in 20th-century American comic books? You can see that their thick chests are exaggeratedly puffed out, while their legs are drawn long and thin in contrast. A symbol like the Oscar trophy doesn’t have much detail, but it’s a handsome male silhouette that anyone can see.

The wide, firm pectoralis major muscle, the thick torso, and the vertical, sturdy beauty that seems to flow down to the ankles are representative of the male aesthetic. This may not be an aesthetic only for Westerners. When we express or show off our confidence, or when we have to show our will and ambition in the face of difficulties, people instinctively try to puff out their chests. However, when we are scared and cower, our posture lowers, our shoulders rise, and we instinctively protect our necks.

This is clearly revealed in the process of men's clothing development over a long period. By consistently emphasizing the chest, you can sense the intention to hide the weak point, the neck. This tendency is especially evident in exaggerated periods such as the Baroque. However, simple display tends to lose elegance. Therefore, decorations and clothing gradually evolved to hide the intention and reveal a sense of beauty. The classic suit is a classic that has been completed in this way.

The suit invented in England was made based on this masculinity, and was made to suit the uniquely British ‘manly’ aesthetic and culture. At the time, the British Empire was a military powerhouse, but it seems that there was also a longing for European classical culture. When their children reached a certain age, the upper class sent them on a school trip to confirm and experience the literature they had learned. This was the Grand Tour (gran torismo) from England to France, across the Alps, and on to Rome, Italy.

Before the railroads were built, this was literally a difficult and 'grand journey'. Those who finished the long school trip would rest in Naples, a famous resort in Europe, and prepare to return to their home country. The Grand Tour also meant graduation and coming of age, so the children of noble families needed men's clothing that would express their maturity. Of course, the European nobles who visited the resort also wanted to wear new clothes suitable for the warm climate of southern Italy. So the British suit technique was also introduced to Naples.

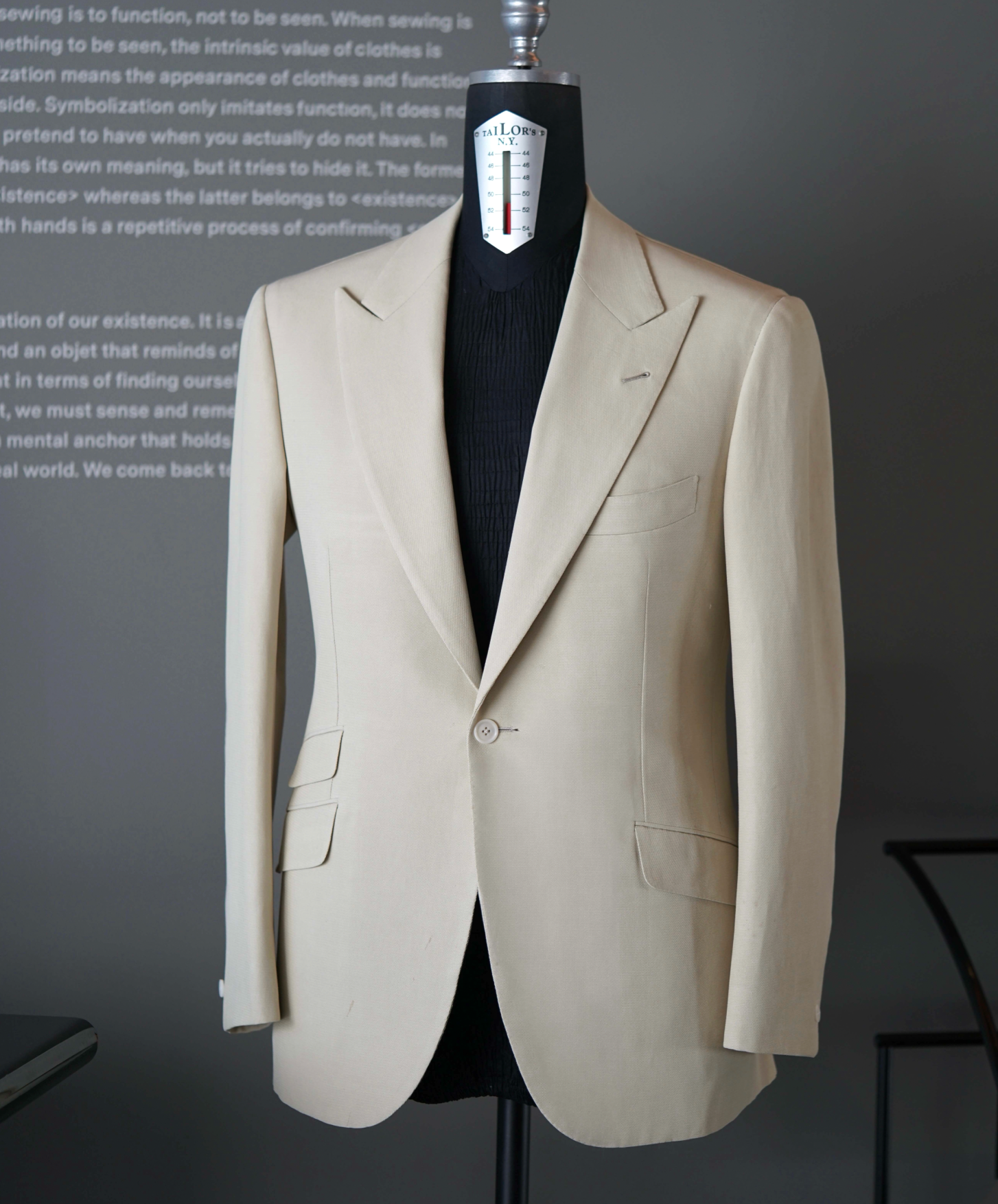

In the eyes of Italians, British suits were masculine, but not beautiful. The first place where change began was a bespoke atelier called 'London House'. Gennaro Rubinacci and Vincenzo Attolini began to create new designs using soft and light Italian fabrics, such as suit shoulders that looked like shirts and curved pocket details. These changed details gradually developed into clothes that could fully express classic masculinity, that is, clothes that emphasized the volume of the body and made it look three-dimensional.

The Neapolitan maestros called this new development of clothing scuola nuova. It was a chemical reaction between the long-standing aesthetic of drape, symbolized by the chiton and toga, and the humanistic spirit of the Renaissance, which met the perfected form of menswear. The Neapolitan maestros wanted to make clothes that thoroughly conformed to the body, and they began to devote all their capabilities to making clothes three-dimensional. And the idea of making clothes three-dimensional and fitting them to the body was an important factor in the classic bespoke focusing on hand sewing.

Bespoke suits that add flavor to the atmosphere

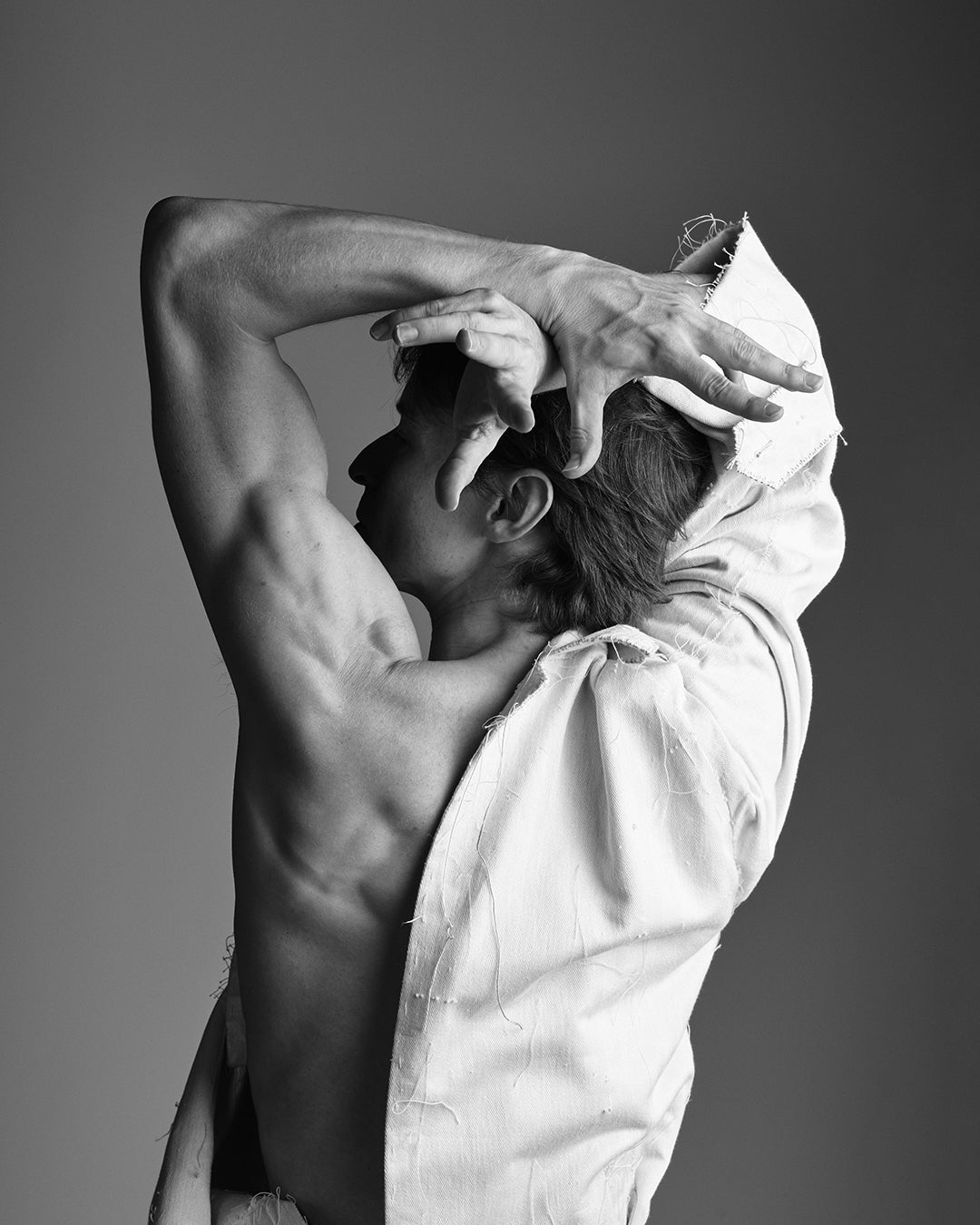

When designing suits that flow and conform to the male body, the maestros of Naples pondered over how to bring out the volume of the chest. How three-dimensionally this part could be expressed was a question directly related to classical masculinity. The specific details that determine the volume of the chest are the chest, lapel, and sleeve head. When these three details have abundant volume, masculinity is well brought out. However, it is not easy to create a drape with soft and weak fabric while at the same time bringing out the three-dimensionality of the details.

So the suit is made of fabric and interlining. Weaving different fabrics together to create a shape that wraps around the body. If we were just simply sewing the ends together, there would be no point in going through the trouble of hand sewing. What we are trying to create is a deep and solid three-dimensional effect that appears when the entire interlining is tightly attached to the fabric and stitched. If we simply glue it together or sew it with a machine, it will be fixed stiffly and not natural. Weaving the interlining and fabric with tight hand sewing creates a soft and elastic three-dimensional effect.

The dynamics of three-dimensionality in clothing arise from the close relationship between the fabric and the interlining. The principle is common sense. A three-dimensional object inevitably has an inside and an outside. Let's think of the inside and the outside of a three-dimensional curve as the fabric and the interlining, respectively. If the two lines move at the same speed, it is a straight line. If the inside line moves more slowly, it becomes a curve. If the outside line becomes longer, it will bend inward. That's right. If the interlining is even one thread shorter than the fabric when sewing the fabric and the interlining, you can create a three-dimensional curved surface.

It is to stack numerous stitches by holding the flat fabric and wick by hand, and pushing and pulling little by little. By making a certain curve in this way, each individual curve is smoothly connected to each other. Here, a single stitch is a point with a three-dimensional position value. Points of different heights come together to form a three-dimensional surface with a sense of volume. The closer the intervals, the smoother the surface. The principle is common sense, but the work is not common sense at all. This is the core of the famous Neapolitan new school (scuola nuova).

Our bodies are three-dimensional. Good clothes should wrap the body in three dimensions. However, there is no machine that can implement this yet. I am not talking about the degree of creating curves by catching dart lines or waistlines. In order to create the volume necessary to express the most elegant masculine atmosphere, that is, a rich chest, lapel, and sleeve head, hand sewing is the only way.

Hand sewing is not just a decoration to get a high price or to show off the handmade look. There is a clear reason and purpose for it. Surprisingly, many tailors say, " Why are you putting so much effort into something that is not even visible ?" But at least for us, the results of the work are clearly visible, so we have no choice but to spend the most time on it.

writing | Kim Dae-cheol