The word “masterpiece” originates in in the field of crafts. In the medieval guilds, where many craftsmen and apprentices gathered to produce craftworks, the word “master-piece” was used to distinguish the works made by the master of the guild. The master was a craftsman with much accumulated experience and skill. What really distinguishes the ordinary artisan from the master? I believe that a fundamental difference in perspective separates the two. It is a small but distinct difference that creates a masterpiece and furthermore develops the ideas and trends of an era.

Modern Danish design gave birth to the movement called Mid-Century Modern. At the starting point is Hans J. Wegner (1914-2007). He was a designer who carried on the innovation of the Bauhaus and a master craftsman who worked as a carpenter. That famous piece of furniture known as 『The Chair』 is Wegner’s creation. His masterpiece is considered to be the perfect connecting piece in the logic of modern industrial design, based on the craftsmanship that followed the past apprenticeship system of handcraft.

Wegner’s philosophy extends beyond the field of wooden furniture. He led the global trends of his time, and has been enlightening many craftsmen to this day. Wegner also had a profound influence on the foundation of Atelier Lerici. Perhaps he will bring important insight to your field also. He is not just an artisan working with wood but a philosopher and master who continues to work on a task that can “never be completed” through endless refining.

Hans Wegner at the age of 14 (third from the left) during an apprenticeship with H.F. Stahlberg in Denmark (1928) ©

"A chair is to have no backside; it should be beautiful from all angles."

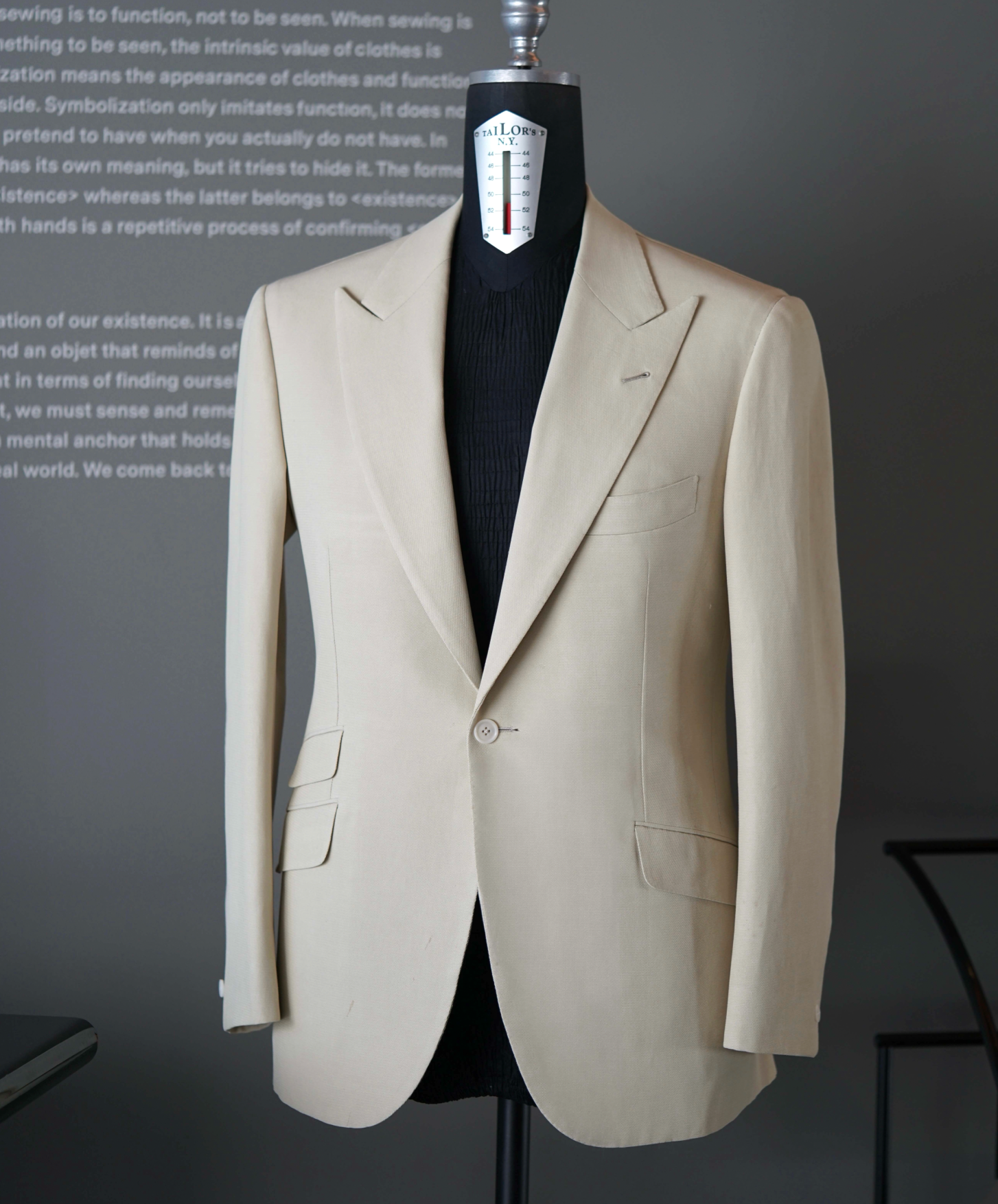

Wagner says that a craft item should not have a backside. This means it should be beautiful when seen from any angle. To choose a beautiful chair, he tells us to turn the chair upside down and look at the bottom. This means that you can trust a chair that has been made with care right down to the parts that are usually unseen. This is why a work made by a master craftsman is different. Wegner knew that quality was determined by the parts that people do not notice and the small details that they easily overlook.

This is the age of production, and everyone is concerned only with the logic of production. Achieving and expressing something in an invisible part may be nonsense in this regard. However, craftworks are different from manufactured goods. All parts of a craftwork must be made with consistency. Invisible parts and parts that can only be seen by turning the object upside down must have the same degree of finish. The viewer should not feel that the front and back, top and bottom are any different. There is no beginning or end to the design, so it should have the same feel when seen from any direction.

This view has had a great influence on Lerici’s tailoring. There are a lot of such “backsides” on clothing. All the small and minor details such as the inside of the collar, the fold at the end of the sleeve, the way ornamental buttons work, or the back of the pockets are all backsides. Giving the same level of finish to these invisible backsides and important parts like the lapels and shoulders means a dramatic increase in production time. However, if a garment is made as it were an art object, then these backsides are not small and trivial at all.

"A chair is only finished when someone sits in it."

These words were a very powerful maxim in furniture design at the time. Wegner made it clear that the purpose of a design is determined by the user and emphasized the need for interaction between the user and the design. In fact, his Round Chair became famous in 1960 through a televised debate between the U.S. presidential candidates Nixon and Kennedy. Wegner designed more than 500 chairs in his lifetime, but each chair was only finished when someone sat there.

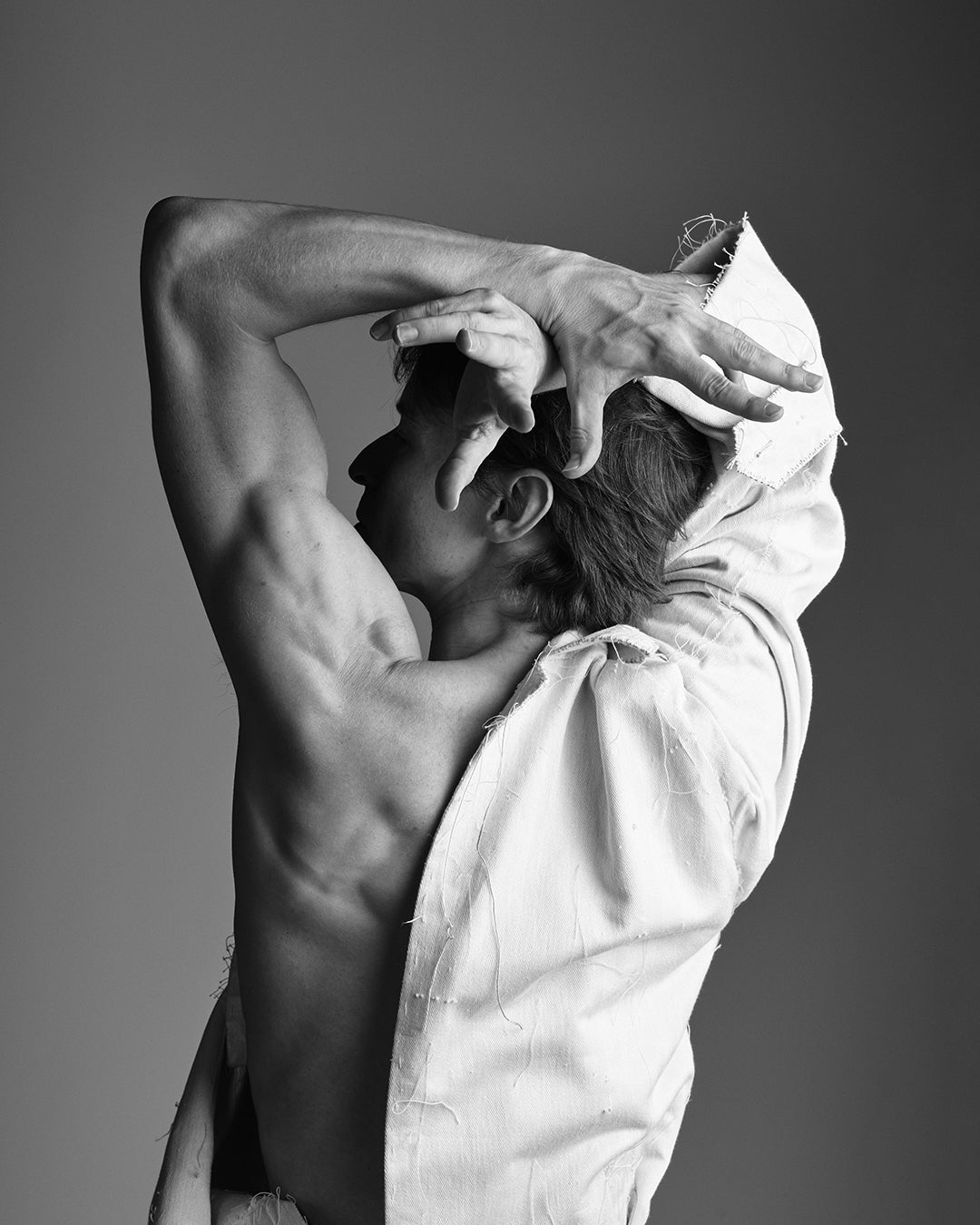

When applied to tailoring, Wegner’s maxim is somewhat new. This is because the most important premise of a bespoke garment is “to make it to fit the person.” But is that really how it is done? Today, tailors take measurements and produce a wide range of clothes but seem surprisingly reluctant to make the garments fit the wearer’s body. They place the fabric on a flat surface and join the pieces in straight lines with a sewing machine. It’s because of the logic of production. Working in straight lines is faster and easier. Clothes made this way may look good in pictures but when you actually put them on, they become stiff, as if they were a suit of armor.

Bespoke tailoring is not about making a cylindrical box but forming a torso. In other words, the concept of fit is different. Fit does not mean pinching in the waist to make you look slim. A good suit requires the fabric to flow along the contours of the man’s sturdy physique. To make flat fabric flow along the curved surface of the human body, it must be carefully shaped with sewing. This is the role of needlework. Why do craftsmen sew with the garment on their knees or using a mezzaluna (crescent-shaped wooden frame)? It’s because the clothes must bend according to the curves of the body.

first presidential debate in 1960

"The use of materials was clear and lucid, the fervor of the makers was evident in the craftsmanship, and the idea underlying the composition was clear and consistent."

Wegner said he could identify any chair he had designed just by looking at the parts. The theme of any one design is consistently applied to even the smallest parts. In this regard, he once said, “It is important to clarify the subject and apply it to all the parts.” This means there is a clear connection between the theme and the details.

A craftwork is not just a beautiful work of art. It contains a logical structure. There must be a reason for the overall structure of the item, the way it is made and the details. The designer must be able to explain it all. When it is hard to explain why such a material was chosen and why it was made a certain way, the design in question is not a proper design. This is probably the issue that troubles all craftsmen until the end.

Clothes also have a logical structure. This is a different matter from style. For example, historically there have been a great variety of styles in which the shoulder line can be made. A single style may involve various techniques, and even with the same style, the way it is applied varies from one part to another. Delving deeper into this matter, you will come to understand that the order and direction of sewing has a logic and unseen purpose developed over a long period of time.

There is also a logical order in sewing. Making clothes is not just the process of sewing pattern pieces together. Depending on the shape of each pattern piece, a certain type of sewing has to be used, and everything logically changes according to the function and the rhythm of the design. So we interview the wearer, take measurements, and make the pattern, keeping in mind that everything in the making process is connected. If these logical steps are ignored and omitted for the sake of production efficiency, subtle nuances will cause an irreversible emptiness in the finished product.

Chair JH503, The Round Chair, 1950. Design Hans J. Wegner ©

"The chair does not exist. The good chair is a task one is never completely done with."

This is what Wegner said when he released his famous Wishbone Chair in 1949. Although critics praised it as close to the perfect chair, that is how he responded. Wegner went on to say, “I wanted to completely dismantle the style of the old chair and have the chair reveal itself purely as structure.” The following year, Wegner designed The Chair, which is called the most beautiful chair in the world to this day.

I believe Wegner was a master who was technically and philosophically close to perfection. But he never stopped exploring possibilities. It is hard to say that this was simply the expression of humility. Later, when people asked Wegner how he had given rise to modern Danish design, he answered that “It was a continuous process of purification.” By this perhaps he means technically “refining,” but I would like to think of it more as religious “purification.”

In an age of abundance, paradoxically we are inundated by low-quality goods. Greedily we consume resources, repeatedly spending and throwing away. In this age, Wegner talks about the attitudes and roles we should adopt. Now, how should craftwork be carried out? Where are we really going? We don’t know the answer yet, but we hope to draw close to another case of perfection someday. Like Wegner’s beautiful masterpiece.

Writer Kim Dae Chul